Boston Sex Therapy Notes: Physically Violent Home Affects Sexuality

Posted on September 22, 2014 by Aline Zoldbrod

Greta*, a thirty three year old woman sat in my office, nervously fidgeting with her hair.

“I’m having terrible relationship problems. I’m not sure what’s going on, but it’s making things really bad with my boyfriend. This is the first time I have ever lived with someone. And six months into the relationship, for some reason, I stopped wanting to have sex. I began to feel that it bothered me to be touched… I felt like I was crawling out of my skin. …Actually, now that I think of it, I’ve had trouble having pleasurable sex my whole life.”

After several decades of hearing stories like this, I wait to see which of the possible next shoes drops. Unsurprisingly, to me, the issue isn’t that she doesn’t love her boyfriend. She does. And it’s not that he’s a bad lover. He’s a good lover. She had never been sexually abused, molested, or raped. What had happened to her, though, is that she had been a victim of repeated physical violence at the hands of her mother, along with emotional abuse from her dad.

It’s this non-sexual family abuse that has caused her sexual problems. This is a very common story, I’m sad to say.

We live in a violent society, and physical child abuse occurs to scores of children and adolescents every year. It’s minimized, because “child abuse” is a legal term, and most abusers are not reported. It’s hard to get statistics that sift out just physical abuse, because many different kinds of abuse tend to cluster together in dysfunctional families. In one single family, you could have emotional abuse, neglect, physical abuse, physical violence between the parents, and/or literal sexual abuse. But literal sexual abuse is not the most common kind of abuse, actually. What you need to know is that in huge research studies, when people were asked direct questions about their experience that got around their emotional defenses against seeing themselves as “victims”, more than half of people studied reported familial violence, abuse and neglect! And among my Boston sex therapy patients, many have sexual problems caused by physical violence, neglect, and emotional abuse, as those who have problems because of overt family-of-origin sexual abuse.

People don’t talk about the physical abuse that has been heaped on them as children and teenagers. They normalize it; they minimize it. It’s just too painful to admit that your parents, who are supposed to be the people who love you best of all, instead treated you worse than they treated the family dog, like you are a piece of garbage, worthless. It’s terribly painful to admit that you’re a victim of family abuse. Abuse is what has happened to other people… It’s way, way worse than what happened to you.

Mostly, the injuries go unrecognized. Everyone and everything colludes in denying how widespread violence against children is. One of my patients, whose own parents had repeatedly, harshly abused her and her sibs throughout childhood, said, “Child abusers should be shot.” Another patient told me that as a young adult, she told her mentor at church about her parents’ physical abuse of her. Since her parents were seen as upstanding members of the church, this woman said, “Well, you have told me this information, but of course, I will never raise this topic with you again.” And she never did.

It surprises people to hear that there are many kinds of family-of-origin abuse and violence other than actual, literal, sexual abuse which cause profound sexual problems in both men and women. It also surprises my patients who have survived physical and emotional abuse and neglect.

Let me tell you a little more about Greta’s story:

“Dad was emotionally abusive. He would get into our faces, right up in them, and he’d scream and yell. He did not literally hit me, per se, but he touched me really harshly. Mom would get really furious with me, and she’d grab me by the face and scratch me with her long fingernails… Even as a child, I was opinionated. At the kitchen table, I’d be mouthing off and my mother would whip around and put her fingernails into my cheek. It was inconsistent. Sometimes she’d do it, sometimes she wouldn’t. I can remember, by the third grade, fantasizing being out on my own, what kind of job I’d have, moving out of the house.”

If you grow up in a loving, affectionate home, with stable, dependable, highly functioning parents who know how to express love through appropriate touch, your associations to touch are positive. Touch means safety, comfort, that one is lovable, that one’s body is adorable. Touch is fun, and touch is kind. Touch is relaxing. Touch makes bad feelings go away. The kinds of messages that are transmitted through touch, particularly when one is upset are wonderful messages. Consider these positive messages:

“Shhh”, “Tomorrow is another day”, “it will be ok,” “We’re in this together,” “You’re safe,” “I’ll protect you,” “I love you.”

One of the common effects of experiencing physical violence in your family is that it changes your associations to touch. And the trouble is, these upsetting memories of bad touch are so excruciating to remember, so dangerous, that they are stored in your body, and not in a very linear and rational form, but as “implicit memory,” split off, dissociated from conscious memory.

Touch is ground zero in having sexual pleasure in an ongoing, intimate relationship, particularly for women. (When young, men’s testosterone levels are so high that they can power through bad stored feelings and just focus on their automatic erections and having a good release. But as testosterone levels drop as men age, the old ghosts of physical abuse begin to appear.)

Greta had none of these good memories about touch. She said, “Dad never hugged. I was never the girl sitting on Dad’s lap. I only got touched when I was doing something wrong. The only time Dad touched me is when he was angry and out of control.”

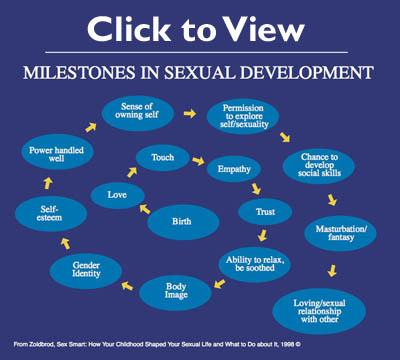

In the mid 1990’s, I began to develop some techniques for working with people who have sexual problems caused by physical and emotional violence and abuse. One of them is a list of positive and negative associations to touch.

Here are Greta’s associations to touch from the word list:

- Controlling

- Out of control

- Awkward

- Tense

- Discomfort

- Jumpy

- Holding breath

- Boring

Greta reports that she does not like kissing, and she does not like having her face touched. She always feels she has to be in control during sex. She wants to be on top—that’s what feels safest. And she does not want to be touched. “I’d rather be the one who is touching.” Not surprisingly, she has never been orgasmic.

So for Greta, what is stored in her body, unconsciously, is that being touched is unsafe and frightening. If she closed her eyes and focused on sensations, who knows what horrifying memories would break through? Rather than be able to let down her guard and let her boyfriend touch her gently and tenderly, so that arousal builds up and she feels great pleasure, if she “gives in” to him, she holds her breath and waits for it to be over.

The happy ending to this story is that if you’re like Greta, if you recognize yourself in this story, and you want to tackle the trauma of growing up in your family, there are targeted therapies that can help you reprocess all the feelings of danger you have in your body. Several body-oriented therapies can be very helpful—particularly Sensorimotor Psychotherapy and Somatic Experiencing (S.E.) it IS possible to reclaim your sexual self.

Aline Zoldbrod Ph.D. is a renowned Boston sex therapist and psychologist and the author of the award winning book SexSmart: How Your Childhood Shaped Your Sexual Life and What to Do About It (1998). You can find out more at http://www.SexSmart.com.